Understanding Intersectionality in Canada's Opioid Crisis

Kajanan Dayaparan

As Canada faces a severe opioid crisis, it becomes imperative to grasp the complex interaction of factors such as demographics, socioeconomic status, and utilization of services among individuals facing opioid overdoses. This understanding is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies. Between January 2016 and June 2022, Canada recorded a staggering 32,632 apparent opioid toxicity deaths, signalling an urgent need for targeted interventions1. Many others have also faced life‑threatening medical emergencies such as respiratory depression, overdose-induced coma, and severe injuries including accidental trauma or falls due to impaired cognition and motor function (2).

Figure 1: Age Breakdown of Opioid Deaths in Canada, 2016–2021 (Hatt, 2022)

A comprehensive review of provincial and territorial surveillance reports from Statistics Canada reveals specific subpopulations bearing the brunt of the opioid crisis. Those without stable housing, incarcerated populations, and First Nations people are disproportionately affected. A national study of opioid poisoning-related hospitalizations reported higher hospitalization rates among those with lower income and education levels, the unemployed, Indigenous individuals, lone-parent households, and those spending more than half of their income on housing. Notably, a study in British Columbia unravels the heterogeneous nature of the population experiencing opioid overdoses, emphasizing the importance of understanding diverse backgrounds and experiences within this crisis (1).

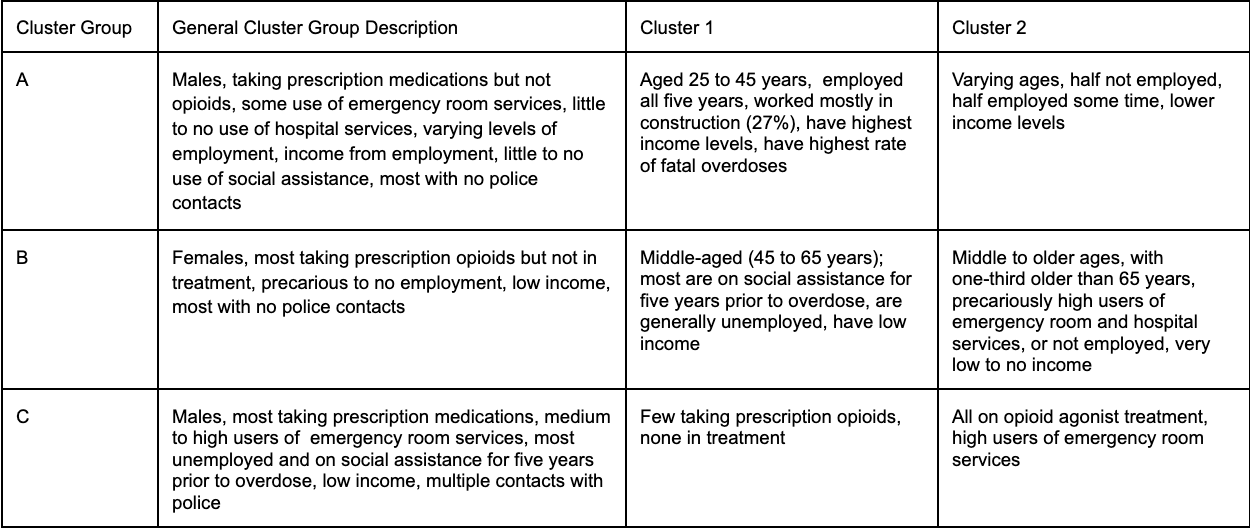

To delve deeper into the distinct characteristics of individuals facing opioid overdoses, a study conducted a cluster analysis using an integrated dataset from Statistics Canada's British Columbia Opioid Overdose Analytical File (BCOOAF). This dataset amalgamates information on demographic, socioeconomic, healthcare service use, and police contacts. The study identified six distinct clusters through unsupervised machine learning, with three overarching groups (A, B, and C) and two clusters in each. Group A primarily consisted of employed males, with Cluster A1 showing stability in employment, higher income, and a higher prevalence of fatal overdoses, especially in construction. Cluster A2, on the other hand, exhibited precarious employment and lower income. Group B, dominated by females, is characterized by middle-to-older-aged individuals (45 to 64 years) receiving prescription opioids, facing socio-economic challenges, and showing a higher prevalence of opioid agonist treatment (OAT). The primary distinctions between Clusters B1 and B2 lay in age profiles, the proportion experiencing fatal overdoses, income levels, and healthcare service utilization patterns, with Cluster B2 exhibiting worse outcomes in these aspects. Group C comprises younger males (24 to 44 years), displaying high unemployment, social assistance receipt, multiple police contacts, and diverse OAT usage patterns between Clusters C1 and C2 (Chu et al., 2023). The main distinction between Clusters C1 and C2 is prescription opioid usage, with only 7.0% of individuals in Cluster C1 receiving any opioid medications compared to all individuals in Cluster C2, where 89.2% were prescribed opioids, predominantly as part of OAT(1).

Table 1: Cluster group by general and cluster description (Chu et al., 2023)

The cluster analysis approach provides insights into the multifaceted nature of opioid overdose dynamics, offering profiles that can guide targeted prevention efforts. The study's findings align with existing evidence, emphasizing the importance of considering employment stability, income levels, and health service use when crafting interventions. Notably, these findings underscore the importance of considering diverse factors when designing targeted prevention programs for different subgroups within the population affected by opioid overdoses (1). Community-based harm reduction outreach strategies play a vital role in addressing the opioid crisis by integrating services into diverse settings, such as workplaces, churches, and community spaces. Implementing initiatives such as accessible drug-checking services, harm reduction vending machines, naloxone and fentanyl test strips, would enhance equitable access to life-saving resources and reduce overdose rates, especially among marginalized populations (5).

Moreover, increasing access to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD), like buprenorphine, within doctor offices can combat stigma and promote the acceptance of MOUD as a vital part of treatment plans. Addressing the gender gap in prescription rates ensures equitable access to these medications for both women and men, ultimately contributing to mitigating the opioid crisis (4). Lastly, several studies reveal racial disparities in opioid prescriptions and under-treatment of pain in minority populations, suggesting that biases may influence physician decisions in pain management prescriptions. Addressing racial disparities in opioid prescriptions and under-treatment of pain requires comprehensive approaches that acknowledge both individual experiences and systemic inequities. Systemic changes are required to combat biases and promote health justice in opioid misuse interventions (3). Understanding these clusters can inform future policies and program planning, ultimately contributing to more effective prevention and harm reduction initiatives in Canada's fight against the opioid crisis (1).

References

(1) Chu, K., Carriere, G., Garner, R., Bosa, K., Hennessy, D., & Sanmartin, C. (2023). Exploring the intersectionality of characteristics among those who experienced opioid overdoses: A cluster analysis. Health Reports, 34(3), 3+. https://link-gale-com

(2) Hatt, L. (2022). The Opioid Crisis in Canada. Library of Parliament. https://lop.parl.ca

(3) Persmark, A., Wemrell, M., Evans, C. R., Subramanian, S. V., Leckie, G., & Merlo, J. (2020). Intersectional inequalities and the U.S. opioid crisis: challenging dominant narratives and revealing heterogeneities. Critical Public Health, 30(4), 398–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2019.1626002

(4) Pollock, D.W. (2022). Intersectionality of Stigma: Gender and Opioid Use Disorder. Center for Addiction Outreach and Research. https://storymaps.arcgis.com

(5) Valasek, C.J., Bazzi, A.R. (2023). Intersectionality and Structural Drivers of Fatal Overdose Disparities in the United States: a Narrative Review. Current Addiction Reports, 10, 432–440. https://doi-org.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/10.1007/s40429-023-00506-2